Bridging Eras: Tulsa’s Southwestern Bell Main Dial Building and the Architecture of Modern Communication

In the roaring 1920s, as Tulsa swelled with oil wealth and ambition, a quiet revolution was taking shape behind the scenes, one that would forever change the city’s soundscape. Gone were the days of operators patching calls by hand. In their place came a new frontier: automatic dialing. At the heart of this transformation stood the Southwestern Bell Main Dial Building, a structure that did more than house telephone equipment. It embodied Tulsa’s transition from a frontier oil town into a modern metropolis—architecturally, technologically, and culturally.

Completed in two pivotal phases—1924 and 1930—the Main Dial Building was more than just a utility hub. It was a statement of progress. When the original two-story facility opened in March 1924 at Fifth Street and Detroit Avenue, it marked the beginning of Tulsa’s dial telephone service. This was no small feat. Until that point, phone calls required human operators to manually connect lines. By investing in a fully automatic system, Southwestern Bell propelled Tulsa to the forefront of telecommunications in Oklahoma.

The transition to dial technology was eagerly chronicled in the local press. On November 1, 1924, the Tulsa Tribune proclaimed the operator-connected method “old-fashioned,” highlighting the dramatic shift in everyday communication. Public curiosity was piqued. Southwestern Bell opened its doors to the community, allowing Tulsans to tour the switch rooms, marvel at the electromechanical machinery, and learn how to use the new dial phones—an innovation that, for some, seemed as magical as it was mechanical.

Architecturally, the 1924 building reflected Southwestern Bell’s conservative corporate identity. Designed in a restrained Florentine/Italian Renaissance Revival style, the façade was clad in buff brick with white terra cotta trim. Arched first-floor windows framed in cream-colored terra cotta gave the building a dignified, almost cathedral-like presence, subtly reinforcing the notion that telephony was the new civic religion of progress. Yet, even in its conservatism, the building hinted at future ambition. Its steel frame and deep foundation were engineered to support up to eight additional stories—an architectural bet on the city’s explosive growth.

And grow it did.

By 1929, the dial building was bursting at the seams. Subscriber numbers had nearly doubled, and Tulsa’s position as a regional communications hub was solidifying. Southwestern Bell responded with a bold $1.5 million expansion project during the onset of the Great Depression. Completed in January 1930, this new chapter was not just about capacity—it was about style.

The four-story addition transformed the building into a six-story icon, embracing the Zigzag Art Deco aesthetic that had come to define late-1920s Tulsa. The expansion, designed by Southwestern Bell’s chief architect I. R. Timlin, reflected a marked shift in public taste. Gone was the conservatism of the Renaissance Revival. In its place rose a sleek, upward-reaching composition of stepped vertical piers and geometric terra cotta ornamentation. Repeating chevrons and ziggurats in buff terra cotta tiles gave the building a rhythmic energy that drew the eye and the imagination toward the future.

The new Art Deco façade did more than impress. It unified the building’s original base with its modern crown through a careful continuity of material and color. The transformation was seamless yet dramatic—a testament to architectural agility. By adapting to changing styles while respecting its foundation, the Main Dial Building became a rare example of stylistic evolution in situ. Tulsa architect Ted Reeds later described it aptly as a “transition piece,” bridging conservative design with the exuberance of Art Deco.

But the addition wasn’t just for show. Inside, the building now housed critical infrastructure: expanded switching equipment, a toll terminal for long-distance calls, and the endpoint of a new underground cable linking Tulsa with Oklahoma City. The top floors became Southwestern Bell’s divisional offices, giving the company both a technical and administrative command center in the heart of downtown. With this upgrade, Tulsa not only modernized its local service—it plugged itself directly into the national communications grid.

Contemporary reaction was enthusiastic. The Tulsa Spirit, a civic booster publication, lauded the building as evidence of Tulsa’s growing importance in national affairs. The investment by Southwestern Bell, especially during a time of economic uncertainty, was seen as a vote of confidence in the city’s resilience. Citizens and civic leaders alike recognized the building not just as infrastructure, but as an emblem of Tulsa’s forward march.

The legacy of the Main Dial Building has endured well beyond its functional lifespan. In 1984, the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its unique architectural evolution and its critical role in Tulsa’s development. Even today, its façade tells a layered story: the solid arches of the 1924 base speak to foundational utility, while the soaring Deco spandrels of the 1930 addition reflect aspiration, momentum, and style.

As with so many buildings of true historical value, the Southwestern Bell Main Dial Building stands not just as a marker of what was, but of what could be. It is a reminder that even utility buildings, structures meant to hide machinery and manage mundane operations, can carry the aesthetic and emotional weight of an era. In Tulsa, it wasn’t just oil that fueled progress. It was also the dial tone of a modern city, echoing from behind Renaissance arches and zigzag towers alike.

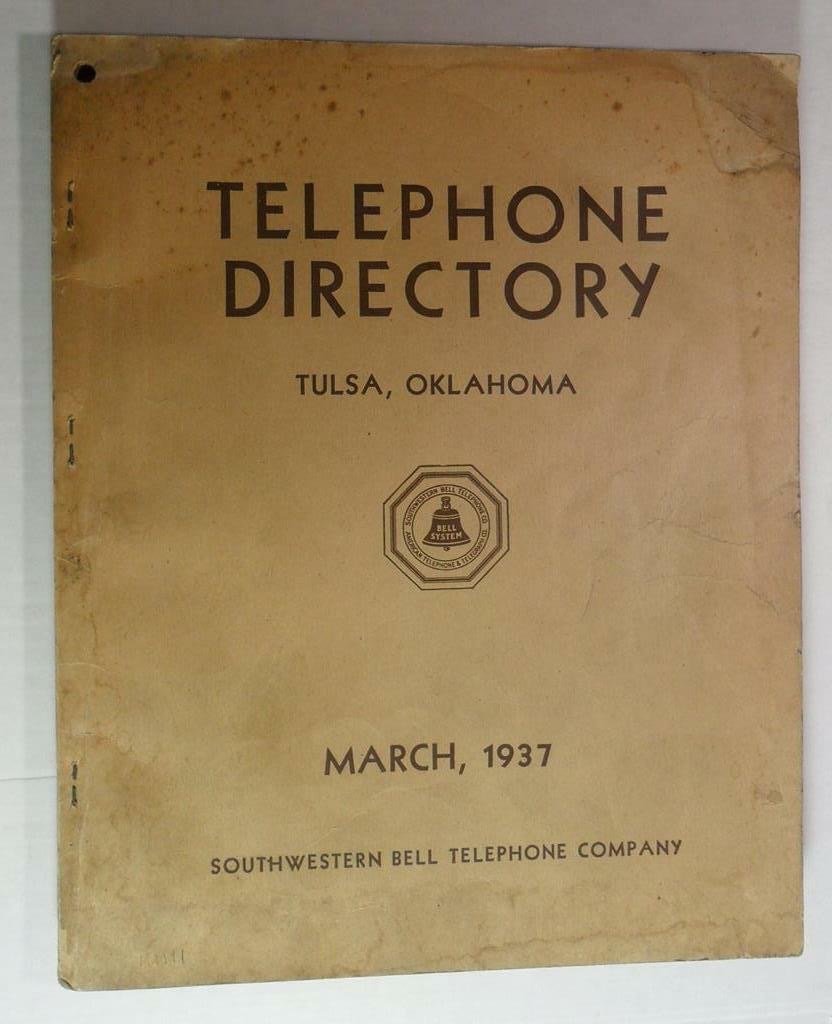

1937 Tulsa Telephone Directory

Published by Southwestern Bell Telephone Company, this historic directory reflects the city's rapid communications growth during the early 20th century.

Southwestern Bell Main Dial Building – Corner View

View from South Detroit Avenue showing the full six-story height and fusion of Florentine base and Zigzag Art Deco upper floors.

Art Deco Terra Cotta Window Spandrels

Close-up of cream-colored ceramic ornament between vertical window bays, showcasing fine Art Deco craftsmanship.

Zigzag Parapet and Cresting Detail

Stylized geometric parapet designs in terra cotta crown the Art Deco expansion completed in 1930.

Southwestern Bell Main Dial Building – Side Elevation

South-facing view highlights the transition between the original 1924 Florentine Revival base and the 1930 Art Deco addition.

Full Façade of Southwestern Bell Main Dial Building

The building's intricate vertical design and mid-century microwave tower reflect Tulsa's evolving communications infrastructure.